Bruce Isaacs Research Provocation: Technologies of New Experience, On Cinema, 3-D and the Imaginary

Cinema’s history – the history of the medium that spans more than a century – is a curious conflation of the technological, the aesthetic, and the affective. Lumiére’s early images of life’s modernity were technologised through the apparatus of the cinematographe, Griffith’s pioneering montage formed early cinema’s narrative tissue, classical Soviet Cinema, Hollywood’s golden age, the European New Waves, the intervention of Avant-garde cinemas in the 80s and 90s– effectively contextualized modes of experience. Cinema was the assemblage of affective phenomena. This is why cinema was never – it could never be – purely an entertainment. It was, more fundamentally, a way of imagining the world.

What is one thus to make of the new 3-D cinematic imaginary? I refer to contemporary 3-D as ‘new’ because mainstream 3-D had previously attempted to imagine the world anew in the 1950s, through a sub-genre of the B-Grade Hollywood picture. This was 3-D’s first studio appearance, its first encounter with a mass culture and a mass cinema industry. Classical studio 3-D, particularly of the Hollywood kind, was both an aesthetic continuation and a point of departure from the mainstream studio genre cinema. Hitchcock attempted to bring 3-D into the studio mainstream through the Warner Bros. production of Dial M For Murder (1954); Warners had had some success with House of Wax in 3-D the previous year. But while House of Wax’s camp horror translated to 3-D’s capacity for excess, the transposition to Dial M For Murder’s conventional, dialogue-heavy situational-drama was less successful. In classical cinema history, 3-D is little more than an affectation, a pleasurable distraction from the evolution of the moving image in 2-D. My first encounter with 3-D was Jaws 3-D in 1984, a film nearer in aesthetic spirit to House of Wax than Dial M For Murder . The 3-D image of Spielberg’s shark was, in the most literal sense, in excess of its 1975 2-D image.

The legacy of 3-D (including Jaws 3-D) is no doubt its hyperbolic aesthetic of shock. We enjoy the thrill of an image dislocated from the itinerary of our own perception – 3-D is more than real. Critics and theorists had always construed 3-D as an affective gimmick; 3-D made affect physical.

But now, in the context of the rhetoric of the new, James Cameron’s Avatar 3-D is projected as new experience, a mediated image so completely, so perfectly immersive, that its cinematic shell is effaced, and the spectator confronts the thrill of cinema produced, post-produced, exhibited and experienced in three dimensions. Spectators are traumatized by the abrupt ejection from the spatially replete eco-world of Pandora; apparently, thousands have sought psychological advice on how to deal with the world of the real, the paltry originary image of the techni-coloured simulacrum. This is why Cameron’s final shot – the Avatar’s eyes ‘opening’ – is both a cliché and an unsettling truth: that cinema ends, credits roll and hyper-real technological worlds cut to black. How does the spectator return to the immersive fantasy when movies end, when 3-D reformulates into 2-D perception, when the fluidity of motion capture in simulated space becomes the jerky, unpremeditated, unmapped movements of actuality?

Contemporary Hollywood projects the 3-D image as new product. Each new 3-D ‘experiment’ (ironically, most studio 3-D cinema eschews aesthetic, and to a large extent, technological innovation) is rhetorically formulated as the intervention of the new. The commoditization of 3-D as experience is nowhere more evident than in Disney’s re-issue of its great Renaissance output of the 90s. The Lion King, wheeled out of the archives in reformulated 3-D in September, grossed 80 million in an initial two-week run. Beauty and the Beast is already in development. Disney, the great commercial conglomerate of a hyper-mediated age, appreciates the unique commercial potential of the re-issue in 3-D.

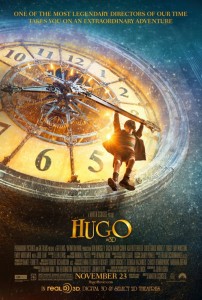

More than fifty years after its brief appearance, it is difficult to project precisely what 3-D is, or what it might be. The thrill of a projectile intruding into the virtual space before the screen is subdued now, or at least, subtly rendered. The new 3-D, inscribed in the conceptual paradigm of James Cameron, renders the technological brush-stroke of cinema invisible. Immersive 3-D experience, for Cameron, should be a hermetic, interior phenomenon. Will this new 3-D alter – or eradicate – cinema as it was once known to the naïve spectator, or as it was once aesthetically inscribed by screenwriter, director, star or studio executive? What will Scorsese, the filmmaker who is most decisively the aesthetic innovator of the New American cinema of the 70s, make of 3-D in Hugo? I read recently that Scorsese described 3-D cinematography as the ‘freest’ mode of cinematic capture. What does the ‘freedom’ of the apparatus of the image connote for the filmmaker who so cavalierly played with spatial and temporal capture in Mean Streets, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull? Can anything in 3-D be as liberating as the complex sequence shot that accompanies Henry and Karen into the Copacabana in Goodfellas? Perhaps even more intriguingly, what will Baz Luhrmann make of Fitzgerald’s evocative image of America in the jazz age in The Great Gatsby (currently in production)? What will Gatsby’s parties look like, animated through cinema’s new vision? Dudley Andrew, in his influential work on the adaptation of literature to cinema, called for the ‘autonomy’ of film; in a sense, Andrew was calling for recognition of the medium’s specificity. Perhaps the theory of the 3-D image in the decade to come must do the same: call for some other mode of conceptualizing cinema, some other mode of image experience, and leave to cinema’s century of image evolution its unique, medium-specific 2-D technological, aesthetic and affective imaging.

Cinema is, and has always been, contamination of one kind or another. Sound contaminated silent cinema, such that four years after the release of Jolson’s The Jazz Singer (1927), silent cinema aesthetics, industry and affect were, truly, a thing of the past. How could Murnau do Nosferatu to diegetic sound? New 3-D is perhaps another contaminative agent that presents, again, unique potentialities of the image. Yet one senses already an aesthetic simplicity, a compositional template from which to extract the 3-D image experience for calculated affective experience. The possibilities for new 3-D are perhaps unfathomable in its infancy, but Scorsese (Hugo), Spielberg (TinTin), Burton and others going to have to work hard to evolve the image as they did (and, to an extent, continue to do) in the late era of 2-D cinema’s formative aesthetic life.

Dr. Bruce Isaacs is Lecturer in Art History and Film Studies at the University of Sydney